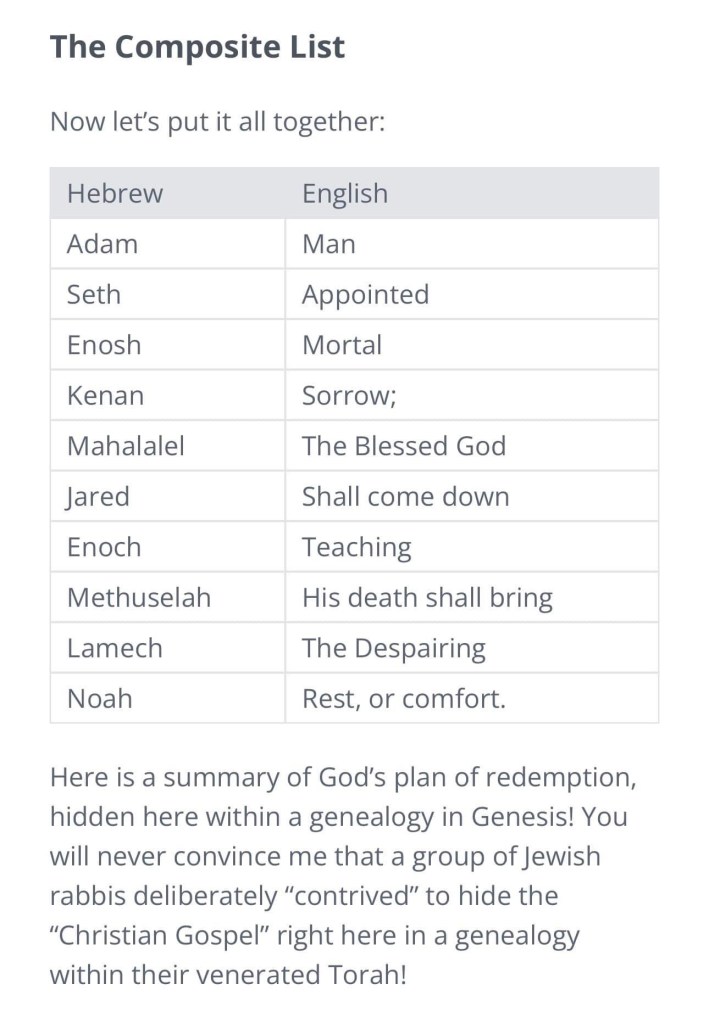

Perhaps you have seen the post that claims the names of the genealogies in Genesis 5 conceal a secret message. The one I saw today had the following chart to illustrate this message. Basically, if you take the leading name of the men from Adam to Noah (Gen 5) you get the hidden message in the chart below: Man Appointed Mortal Sorrow; The Bless God Shall Come Down Teaching; His Death Shall Bring the Despairing Rest, or Comfort. The awkward grammar should be your first clue that someone is making this up.

The cryptographer behind this chart is convince that God’s plan has been hidden in the names found in Genesis 5. However, that is not really how the Hebrew language works.

What the last sentence below the table means is not exactly clear. Is someone claiming that Jewish rabbis clandestinely contrived to hide the Gospel in the Torah? Why would they do that? And how could rabbis do this since Genesis 5 existed long before the time of Jesus?

To be sure, the various authors of the Hebrew Bible engaged in many different kinds of wordplays but with the intent that the reader would catch them—after all they would not be good wordplays if the reader could not share in the fun with the author. For example, one of the best wordplays shows up in the prophet Isaiah who is to called his son “Maher-Shalal-Hash-Baz” (Isa 8:1, 3) which in Hebrew means “quick to the plunder, swift to the spoils.” This is no doubt a symbolic name—can you imagine saying this name every time you called or mentioned your son?

The text, moreover, is quick to fill in the prophetic meaning: “For before the boy knows how to say ‘My father’ or ‘My mother,’ the wealth of Damascus and the plunder of Samaria will be carried off by the king of Assyria” (Isa 8:5). This is more typically what one will find in the Hebrew Bible with any “hidden” meaning, which is not so hidden. Even in Genesis, names often connect with the immediate story being told. (For an extended series of word plays, see Amos 1:8–16, where the various locations sounds like other words that show up in the nearby text).

Adam is both a proper name of the first human male and the class of being (humans) that includes both male and female (Gen 1:27; 5:2). A nice wordplay occurs in Gen 2:7 when Adam (אָדָם) is made from the dirt (adamah; אֲדָמָה). Again, this is quite typical for the Hebrew Bible. But, even at this point, this creates a problem for the chart above since “Adam” can mean human (male and females) or can be a proper name. Context is the best way to determine which connotation is most appropriate; the chart has shown one possibility in the range of meaning for this word. Here, in Gen 5:3, it is a name since it is part of an extended genealogical table.

Seth is a personal name related to the verb that means “put,” “put in place,” “established,” “constitute,” or “make something.” The context, Gen 4:25, is clear about how the wordplay works when Eve announces, “God has granted me another child in place of Abel, since Cain killed him.” Thus, God has given, put in place, a replacement for the son the first couple lost. One need make no more of this than what the text explicitly says. Furthermore, and this applies to all of the names here, no NT writer who makes the point the chart is trying to conjure.

Next, comes the name Enosh. As a noun, instead of a proper noun, it another word meaning “human.” That’s right: it’s another word for man, person, human, or human race. However, it is no more “mortal,” than say the name Adam was. Though “mortal” might be an acceptable translation if one is using the word as an equivalent to human, it is not an adjective as it is being used in the chart above, but a name.

Now, for Kenan. As a noun, this word means a dirge or elegy, a sad song. In its verbal form, it means to chant [a dirge or lament]. It would be incorrect to say that Kenan means “sorrow,” but more correctly the word is related to the noun for dirge or the verb meaning to lament. Again, as with all the names in the genealogical table in Gen 5, the author of Genesis is making a point out of this name or words that sound like it.

Mahalalel is a name that resembles the Hebrew for “praise of God,” not as the chart indicates. Again, the text itself makes no wordplays on Mahalalel, and we should probably show the same restraint. Indeed, in all the places this name shows up in the Bible (Gen. 5:12–13, 15–17; 1 Chr. 1:2; Neh. 11:4; Luke 3:37), no interpretation is ever based on the possible meanings of that name.

The same can be said of the other names in the genealogical list. So let me briefly look at the remaining names in Gen 5: Jared, Enoch, Methuselah, Lamech and Noah.

Jared’s name is similar to the verb meaning “to go down” but neither the text here nor anywhere else makes a wordplay on that name. The chart verbalizes the name to mean “shall go down,” however, if Jared’s name (יֶרֶד) were the verb (יָרַד), it would be translated “went down” (Qal verbs are generally translated in the past tense) As it is here in Gen 5, it is simply a proper name.

Likewise, Enoch’s name (ḥᵃnôḵ in Hebrew) sounds like the Hebrew word that could be translated “to educate, train up,” but could also be translated “to dedicate.” However, in the biblical text, the name refers to a son of Cain (Gen 4:17–18), a son of Midian (Gen 25:4; 1 Chron 1:33), a son of Reuben (Gen 46:9, Ex 6:14, Num 26:5, and 1 Chron 5:3), and, of course, Enoch in Gen 5 (see also 1 Chron 1:3, as well as Heb 11:5; Jude 1:14).

Methuselah is reported in Genesis to have lived the longest of any human. Of course, his father Enoch beats him by not dying at all. But does his name mean or is it related to the meaning “His Death Shall Bring”? The lexicographer (Brown, Drivers, and Briggs) are uncertain as to the exact meaning. Maybe, it echos “man of God,” or it could mean “man of the dart,” as compared to Babylonian sources. In short, no one know what the various components of the name might have meant. So the interpretation of the name in the chart above has been manufactured to fit the desired outcome.

Does Lamech have any connection to the idea of despairing? Again, lexicographers have no clue as to the “meaning” on which this name is based since the root (l-m-k) does not exist in any Western Semitic languages. In others words, outside the name Lamech no other words in Hebrew are built on this root.

Then, finally comes Noah. The name of Noah for does seem to connect to the Hebrew words of rest and comfort, but the application of that name in the context of the genealogy in Gen 5 is explicit in the words of his father Lamech: “He will comfort us in the labor and painful toil of our hands caused by the ground the LORD has cursed” (Gen 5:29). So Noah is envisioned here as a sort of “Messiah” that would somehow reverse the cursing of the ground (see Gen 3:17–18).

All these names, then, form the bridge from the earliest characters in Genesis to Noah. The names themselves are not telling a secret or hidden story but are in the service of the story actually being told in the Book of Genesis. The use of the name “Noah” and the related root nwḥ, meaning “to rest, settle down” is a great example of how the Hebrew Bible does wordplays that are intended to be picked up by the original readers but does not always survive translation into other language.

Thus, in the Flood Story, Noah (nḥ) is to bring comfort (nḥm; in a passive form, “to be sorry for”) from labour (ꜥśh) and toil (ꜥṣb). So the story begins, “And the Lord was sorry [nḥm] that he had made [ꜥśh] man on the earth and it grieved [ꜥṣb] him to his heart”(Gen 6:6). The wordplay with nḥm continues in the next verse: “And the Lord said, ‘I will blot out [mḥh] man whom I have created” (Gen 6:7). Again, “Noah [nḥ] found favor [ḥn] in the eyes of the Lord” (Gen 6:8). Later, Noah begets a son named Ham (ḥm, Gen 6:10), sounding something like “comfort,” but also like “violence” (ḥms): “… and the earth was corrupt in the eyes of God and the earth was filled with violence [ḥms]” (Gen 6:11). “Noah” (nḥ) and “violence” (ḥms) show up again in Gen 6:13 but the wordplay extends to the word “outside” (mḥwṣ) in Gen 6:14, as Noah pitched the ark inside and outside [mḥwṣ].”

Now, the preceding is how a Hebrew wordplay works but it takes some patience and guidance to see them at work, particularly if you have never studied the Hebrew language. (My guide reading the Noah cycle was Isaac M. Kikawada, Anchor Yale Bible Dictionary, s.v., “Noah and the Ark: The Hero of the Flood”).

Now, finally, back to that chart. What more can I say?

In summary, the Bible does not communicates the message of redemption in coded words sprinkled throughout the text. Rather, the Bible is largely a narrative that tells a story. The “story” tells the “story.” While wordplays are present in the Hebrews, these are not always easily available to English readers—the narrative certainily becomes richer when we can see them, but the overarching story of Scripture is not hidden, it is right before your eyes.